-40%

Czechoslovakia banknote - 20 dvacet korun - year 1945 - Karel Havlíček Borovský

$ 8.44

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

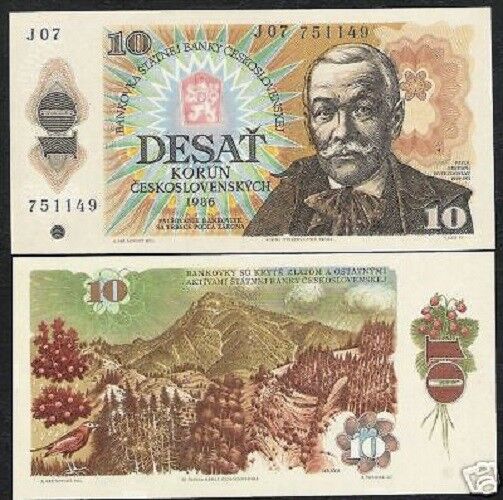

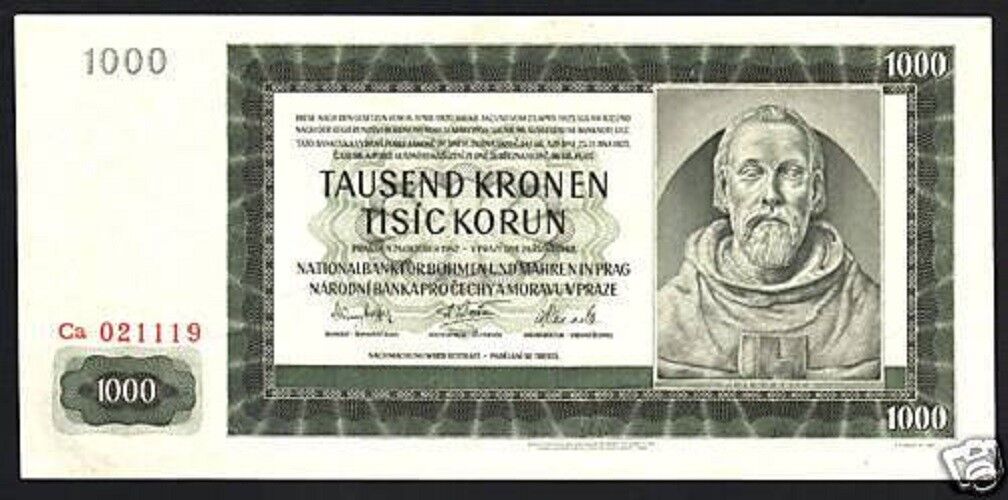

The Czechoslovak koruna (in Czech and Slovak: Koruna československá, at times Koruna česko-slovenská; koruna means crown) was the currency of Czechoslovakia from April 10, 1919, to March 14, 1939, and from November 1, 1945, to February 7, 1993. For a brief time in 1939 and 1993, it was also the currency in separate Czech and Slovak republics.On February 8, 1993, it was replaced by the Czech koruna and the Slovak koruna, both at par.

The (last) ISO 4217 code and the local abbreviations for the koruna were CSK and Kčs. One koruna equalled 100 haléřů (Czech, singular: haléř) or halierov (Slovak, singular: halier). In both languages, the abbreviation h was used. The abbreviation was placed behind the numeric value.

Second koruna

The Czechoslovak koruna was re-established in 1945, replacing the two previous currencies at par. As a consequence of the war, the currency had lost much of its value.

In 1945, four kinds of banknotes of Czechoslovak koruna were introduced. The first were issues of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia, to which adhesive stamps were affixed. Denominations issued were 100, 500 and 1000 korun. The second (dated 1944) were printed in the Soviet Union and were issued in denominations of 1, 5, 20, 100, 500 and 1000 korun. The third were locally printed notes issued by the government in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500, 1000 and 2000 korun. The fourth were issues of the Czechoslovak National Bank, in denominations of 1000 and 5000 korun. The National Bank issued 500 korun notes from 1946, whilst the government continued to issue notes between 5 and 100 korun, the 1 korun note being replaced by a coin in 1946.

Karel Havlíček Borovský (Borová, today Havlíčkova Borová; 31 October 1821 - 29 July 1856) was a Czech writer, poet, critic, politician, journalist, and publisher.

He lived and studied at the Gymnasium in Německý Brod (today Havlíčkův Brod), and his house on the main square is today the Havlíček Museum. In 1838 he moved to Prague to study philosophy at Charles University and, influenced by the revolutionary atmosphere before the Revolutions of 1848, decided on the objective of becoming a patriotic writer. He devoted himself to studying Czech and literature. After graduating he began studying theology because he thought the best way to serve the nation would be as a priest. He was expelled after one year for "showing too little indication for spiritual ministry".

Career

After failing to find a teacher's job in Bohemia, he left for Moscow to work as a tutor in a Russian teacher's family: with a recommendation by Pavel Josef Šafařík. He became a Russophile and a Pan-Slav, but after recognizing the true reality of the Russian society he took the pessimistic view that "Pan-Slavism is a great, attractive but feckless idea". His memories of the Russian stay were published first in magazines and then as a book Obrazy z Rus (Pictures from Russia).

He returned to Bohemia in 1844, aged 24 and used his writing skills to criticize the fashion of embracing anything written in the recently reborn Czech language. He specifically aimed at a novel by Josef Kajetán Tyl. In 1846 Havlíček attained a position as editor of the Pražské noviny newspaper with the help of František Palacký.

In April 1848 he changed the name of the newspaper to Národní noviny (National News) and it became one of the first newspapers of the Revolutionary-era Czech liberals. Národní noviny became popular especially for his sharp-tongued epigrams and its wit. Havlíček was concerned with the preparations of the Congress of the Slavs in Prague. In July 1848 he was elected as a member of the Austrian Empire Constituent Assembly in Vienna and later in Kroměříž. He eventually relinquished his seat to focus on journalism.

Havlíček was a "liberal nationalist" politically, but refused to allow a "party line" to inform his opinions. Often, he would criticize those that agreed with him as much as those that disagreed. He excoriated revolutionaries for their radicalism, but also advocated ideas like universal suffrage-a concept altogether too radical for most of his fellow liberals. He was a pragmatist, and had little patience for those that spent their time romanticizing the Czech nationality without helping it achieve political or cultural independence. He used much of the space in his newspapers to educate the people on important issues-stressing areas like economics, which were sorely neglected by other nationalist writers.

The Revolution in the Austro-Bohemian portion of the Habsburg monarchy was defeated in March 1849 with dissolution of the Kroměříž assembly, but Havlíček continued to criticize the new regime. He was brought to court for his criticism (there was no freedom of the press in the Habsburg's territory) but was found not guilty by a sympathetic jury. Národní noviny had to cease publication in January 1850, but Havlíček did not end his activities. In May 1850 he began publishing the magazine Slovan in Kutná Hora. The magazine was a target of censorship from the start. It had to stop publication in August 1851, and Havlíček stood again at the court to answer on charges of dissent. Again, he was found not guilty by a sympathetic jury of Czech commoners.

Havlíček translated and introduced some satirical and critical authors into the Czech language culture including Nikolai Gogol (1842) and Voltaire (1851).

In the night of December 16, 1851, he was arrested by the police and forced into exile in Brixen, Austria (present-day Italy). He was depressed from the exile, but continued writing and wrote some of his best work: Tyrolské elegie (Tirol Laments), Křest svatého Vladimíra (Baptism of St.Vladimir) and Král Lávra (King Lavra).

When he returned from Brixen in 1855, he learned that his wife had died a few days earlier. Most of his former friends, afraid of the Bach system, stood aloof from him. Only a few publicly declared support for him.

In 1856, Havlíček died of tuberculosis, aged 35. Božena Němcová put a crown of thorns on his head in the coffin. His funeral was attended by about 5,000 Czechs.

Memorials

A monument was raised to Havlicek in Chicago by Czech residents of the city in Douglas Park. The bronze statue by Joseph Strachovsky was cast by V. Mašek in Prague and shows Havlicek in a revolutionary pose, dressed in a full military uniform and a draped cape with his outstretched arm motioning the viewer to join him. The statue was moved to Solidarity Drive on today's Museum Campus in the vicinity of the Adler Planetarium in 1981. In 1925 a biographical film was released.